You can watch a short film about The Paradoxal Compass here.

John Maynard Keynes, economist and architect of the post-war global order, wrote in 1930 that the modern age opened with the ‘accumulation of capital which began in the 16th century… and the power of compound interest is such as to stagger the imagination.’ He added: ‘I trace the beginning of British foreign investment to the treasure which Drake stole from Spain in 1580… every pound that Drake brought home has now become £100,000.’ In 2017 money that’s around £500,000.

This is an economist’s view of what the circumnavigation meant. Many would still agree and there is obviously important truth in it. But already in 1580 there were dissenting views. It may have been ‘the power of compound interest’ which staggered Keynes’ imagination. Other kinds of imagination are staggered by other things. I’ve shown in The Paradoxal Compass, for example, how intensely some on board the Golden Hinde enjoyed watching the unfamiliar marine wildlife they encountered. They did not only regard it as a food source. I’ve shown also how carefully that enjoyment was edited out of the material used for the official narrative. Drake’s treasure did not impress everyone. William Cecil famously refused the ten gold ingots Drake offered him. The Earl of Sussex refused a gift of silver plate. Less famously, the compass-maker Robert Norman wrote a poem in 1581, published, pointedly, a year to the day after Drake’s return, which takes a sceptical look at those who prize treasures brought from afar over the science which has made such voyages possible. The French botanist Carolus Clusius travelled to London in the same year to interview Drake and his crew about the peoples, plants and animals they had met with. Neither gold nor silver nor compound interest is mentioned in the short book he wrote about what they told him.

The Tudor navigators until recently enjoyed a folkloric status in the South West of England, where many of them spent their childhoods. I describe what it was like to grow up around those stories. Any such ‘folkloric status’ is, inevitably by now, shadowed both by the legacy of imperialism and by our present-day environmental predicament. I argue that the time is right for revisiting our assumptions about the explorers. The famous ones like Drake, but the forgotten ones, too, like Stephen and William Borough or John Davis, took more interest in the new environments they encountered than we give them credit for.

The Paradoxal Compass was invented by John Dee in the 1550s to help with navigation in the higher latitudes. The Borough brothers and John Davis were instructed in its use but not much more is known about it. Dee could never raise the money to publish the book he wrote about it and the manuscript is now lost. For my purposes it is largely a metaphor: for the multiple ways in which we struggle to navigate this ever more contradictory world of ours. The book is an exploration of two troubled relationships: the one we all, by now, have with the sixteenth century and the modernity which took hold at that time. It explores also the troubled relationship each of us has with his or her own formative experiences.

It is a book above all about motives and how difficult they are to get at: I argue that these navigators were more at odds, with themselves and with each other, than the official narratives could allow. Drake and his chaplain, Francis Fletcher, for example, are known to have argued furiously while the Golden Hinde was stranded on a reef off Indonesia in January 1580. But the exact nature of their dispute was suppressed in the published accounts of the Famous Voyage. I recreate the scene and re-imagine their disagreement.

I suggest furthermore that the argument which was suppressed then continues now. As an activist and journalist, I have written for more than a decade about marine conservation in the South West, particularly in Lyme Bay. The book concludes with an account of how the Marine Protected Area there came to be established. I explore also its wider significance, both for those who live right next to it and for anyone anywhere who cares about marine habitats and the impact our way of life is having upon them.

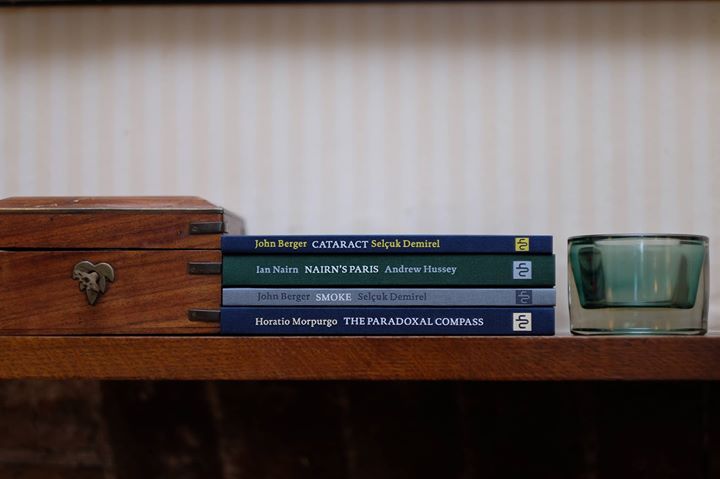

Image by Sebastian Morpurgo

The Sea, the Strangers and the Stories (Erewhon Books, 2015) is an essay on the present migration across the Mediterranean and how Europe should respond. It reflects on a theory about the Odyssey elaborated by the novelist and translator Samuel Butler. He believed he had proved that the poem was written by a young woman living in Trapani, a town in western Sicily. Horatio explores the town, leaving the reader to draw his or her own conclusions about the meaning of Butler’s theory today.

The Sea, the Strangers and the Stories costs £3 at Waterstones

Lady Chatterley’s Defendant and other Awkward Customers (2011), an essay collection, was published by Just Press. Here is the page about it on their website. If you would like to order a copy of this book please do so via the Just Press website – that way your money will go to the people who actually put in the work.

A compelling collection… from a highly intelligent author

Tribune.

You can link here to Belinda Webb’s blog about it.

The whole collection has a freshness and a surprisingness which are a delight… I hope lots of people will read this book – for its vigour as well as its vision.

Ronald Blythe

Two themes are of special interest to me — one is the concern for literary endeavor (in the broadest sense) as a potential seedbank or greenhouse for cultural paradigm shifts, whether in the streets of Cairo and Prague, or in somebody’s head… Another theme that speaks to me is the concern for the place of religious life and thought in our world. This is a vast topic, of course, but I believe you put your oar in with wisdom and compassion.

Taylor Stoehr

I found much to admire and enjoy. I especially liked your critique of Hitchens and Dawkins – you nailed, via Samuel Butler, exactly what is wrong with them.

Jonathan Franzen

I read this book with great interest. I like the trajectory – return to England, Hardy, Dorchester Museum, collateral Olympic damage – very much. Pointing out how the grand project becomes a smokescreen for land piracy is a valuable exercise.

Iain Sinclair on How Thomas Hardy Expressed His Doubt, included in the collection, also available as an Erewhon Book.

How Thomas Hardy Expressed His Doubt by Horatio Morpurgo

How Thomas Hardy expressed his doubt

In search of a more integrated way to write, Horatio Morpurgo turns his attention to Weymouth’s ‘Olympic Road’. As the environmental debate rages, he seeks to extend it beyond journalism, remaining faithful meanwhile to the best traditions of investigative reporting. In a tightly woven narrative, Morpurgo re-visits the controversy surrounding Thomas Hardy’s religious views, looks into the surprising early history of the Dorset County Museum and reflects on his own move to the West Country, each by turn forming part of his response to the new road. Ever more sceptical of consensus reality, he candidly explores the difficulties which beset any attempt to transcend it.